The reaction of consumption to income shocks

2 min

How do we react to an income shock? In the case of a positive shock, do we spend all the money we gain on consumption? And what do we spend it on? Consumer durables or non-durables? Or both? And if our income falls, do we become more frugal?

Kris Boudt, Koen Schoors, Milan van den Heuvel and Johannes Weytjens from Ghent University have investigated these questions. Traditionally, the study of the marginal propensity to consume, i.e. the change in expenditure in response to a change in income, has been subject to several limitations.

In the past, this type of research was mainly carried out on the basis of surveys and macroeconomic observations. The four Flemish researchers have brought something new to the table. What makes their approach unique? The size of their data set.

Belgian households and their consumption reflex

In collaboration with our bank, the researchers were able to access the anonymised earned income of 1.4 million exclusively Belgian households over a period of 12 years. These figures were supplemented with socio-economic and other indicators, making it possible to obtain a representative picture of the entire population[1].

The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) plays an important role in macroeconomic analysis. Among other things, the MPC determines, among other things, the size of the multiplier of income spent. The higher the MPC, the greater the overall positive impact of additional public spending on GDP.

But how is the MPC calculated? It is a percentage change in expenditure relative to a percentage change in income.

Income and consumption

First, the researchers identified several types of income shocks, each with a positive (increase) and negative (decrease) variant. An income shock may be permanent or temporary. And temporary shocks can be recurring or one-off. It may come from a pay rise, a holiday allowance or a special bonus.

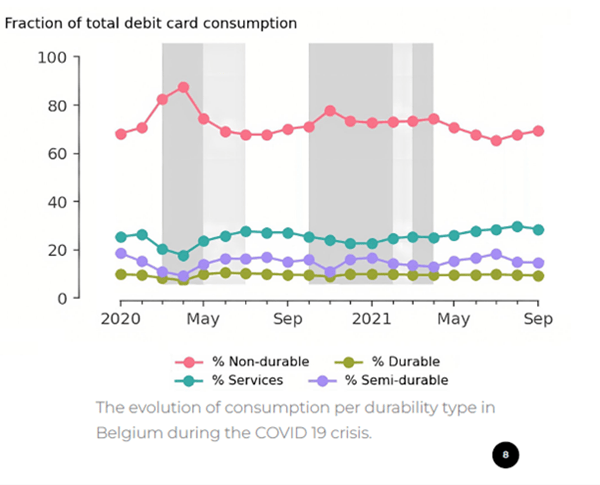

Expenditure was labelled according to the COICOP consumption classification. Four types of consumption were identified: durable consumer goods, semi-durable consumer goods, non-durable consumer goods and services. The graph below shows the relative share of each of the 4 categories in total consumption.

The results

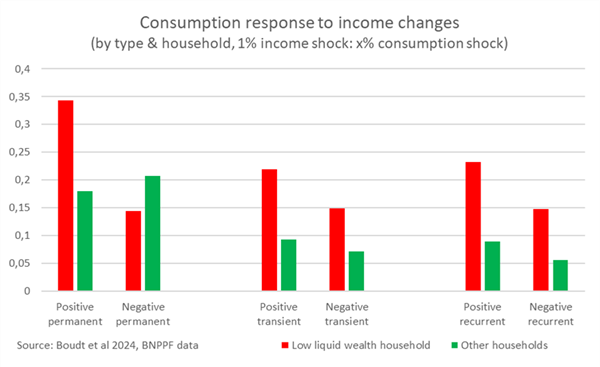

The table below summarises the main findings. A distinction has been made between households with limited liquid assets and other households. It is not surprising that households react strongly to a permanent change in their income.

In line with the literature, wealthy households consume a much smaller share of the increase in their income. For almost all categories, the response to a decrease is weaker than the response to an increase of the same proportion.

However, consumers also react to temporary income shocks. This is interesting because economic theory suggests the opposite. In fact, according to the theory of permanent income, a perfectly rational consumer should compensate for this type of shock.

This may be because such temporary shocks (bonuses, inability to work as many hours as before) are unexpected for most households.

The study provides a good insight into the effects of different income support mechanisms. It is clear that a permanent (costly) increase can have the biggest impact on households with the lowest assets. The difference between a recurring annual income increase and a one-off increase is therefore very small.

[1] It should be noted that the researchers only looked at earned income. For consumption data, the researchers based themselves on the establishment where the purchase was made. This is a good, albeit imperfect, approach to determining the type of consumption.