The IMF warns about public debt

2 min

The IMF has released its latest Fiscal Monitor, which deserves attention as it comes at a critical moment: China is attempting to rejuvenate its economy with a massive fiscal stimulus, while the United States seems destined to live with surging public debt, regardless of who wins the upcoming election on 5 November. The IMF is raising alarms because global public debt has soared over the past five years, heading towards a level equivalent to 100% of global GDP.

A $100 trillion debt

Since the 2008 financial crisis, every major crisis has been partly resolved through increased public spending and heavy reliance on monetary easing – essentially, central banks financing public debt. In its latest Fiscal Monitor, the IMF highlights the significant deterioration in global public finances since the 2020 pandemic, forecasting that global public debt will likely exceed $100 trillion by the end of this year, equivalent to 93% of global GDP.

Throughout its report, the IMF emphasises the urgent need for tougher action to stabilise borrowing in the world's major economies. Public debt, which ballooned during the COVID-19 pandemic, has continued to rise as countries ramp up spending to stimulate economic growth, with the US and China leading this trend. At the current pace, global public debt will reach 100% of GDP by 2030 unless action is taken.

The IMF also criticises the countries with the fastest-growing debt levels for underestimating the magnitude of the measures required to address the issue, particularly when planning for the future. According to the IMF, a significant number of countries are implicated, as those whose debt is unlikely to stabilise account for over half of global debt and approximately two-thirds of global GDP.

Taking advantage of falling interest rates

The IMF singles out the UK, Brazil, France, Italy and South Africa as particularly problematic, warning that “future debt levels could be even higher than projected, requiring much larger fiscal adjustments than currently anticipated to stabilise or reduce them successfully.”

The IMF stresses that countries should take advantage of the current easing in monetary policy to implement well-designed fiscal policies that protect growth and support vulnerable households, using savings from lower interest rates. As inflation declines globally, the IMF considers this an opportune moment for countries to rebuild fiscal reserves. It estimates that the required effort – via tax increases and/or spending cuts – would need to amount to 3% to 4.5% of GDP cumulatively over the medium term to achieve a reduction in global debt.

Revisiting priorities

The IMF also advises advanced economies to reassess spending priorities, increase revenues through indirect taxes where tax rates are low, and eliminate inefficient tax incentives. This is particularly important given that public spending pressures are set to grow in the coming years with the transition to greener energy, ageing populations, and security challenges – costs that are difficult to quantify in many cases.

The IMF’s report coincides with China’s efforts to revive its economy through massive fiscal stimulus and with the US elections just weeks away. Economic plans proposed by Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are expected to increase United States federal debt by trillions of dollars, according to a recent report by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Financial market concerns

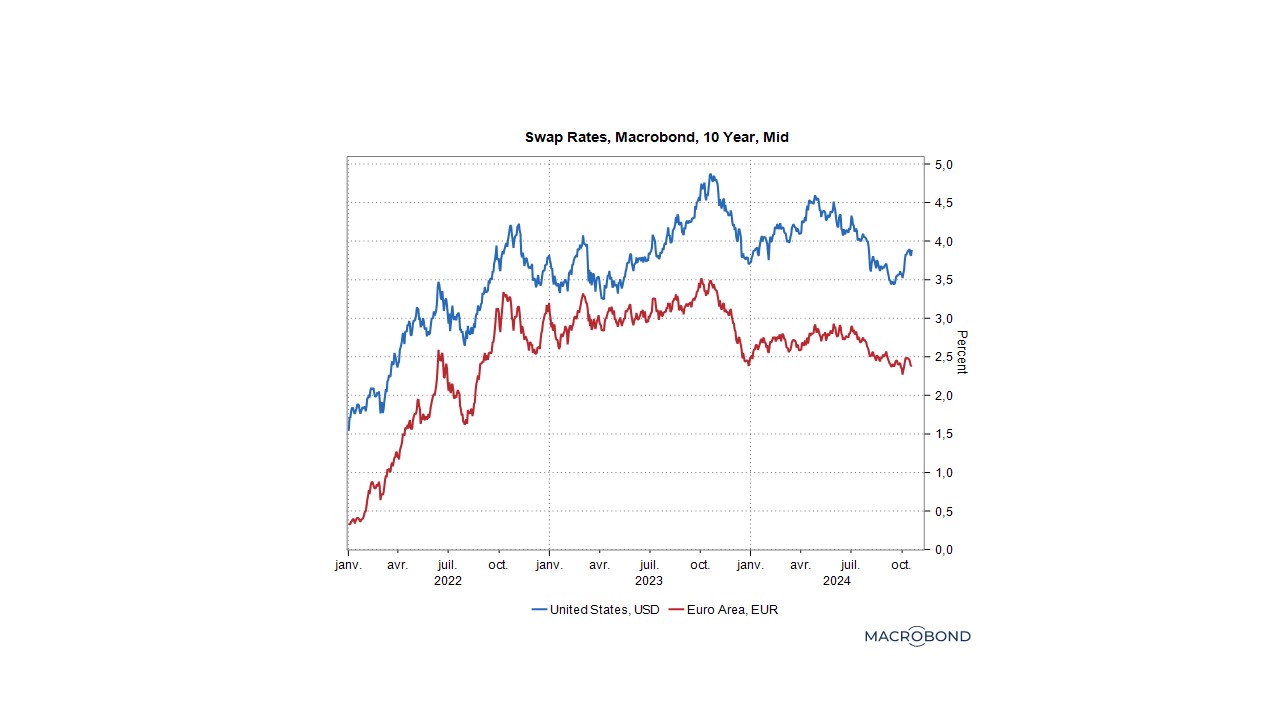

Financial markets are increasingly worried about runaway debt levels, as reflected in the recent mass sell-off of bonds in certain markets, pushing interest rates higher once again.

The European Central Bank (ECB) echoes the IMF’s concerns. The ECB estimates that to achieve a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60% by 2070 – a target originally agreed upon by European nations under the Maastricht Treaty – governments would need to immediately and permanently increase their primary balance (the budget balance excluding net interest payments on public debt).

The path forward will be long and fraught with challenges, but these figures must be closely monitored. Europe cannot afford another “debt crisis,” especially one involving countries with public debt levels ten times greater than Greece’s during its 2011 bailout.

Thus far, long-term interest rate increases have been more pronounced in the United States than in Europe, but there is no guarantee that this trend will continue.