Monetary policy in Europe

2 min

History repeats itself - but not for monetary policy, because the current context is unprecedented.

The least we can say is that 2025 has gotten off to a bad start. Not just due to the impending trade war and the renewed fear of rising inflation in the U.S., but also due to the extreme geopolitical tensions in the Middle East. It is therefore difficult to predict where the EU's economy is headed in the coming months. The European Commission finally seems to be heeding companies' pleas, which are groaning under the administrative burden arising from the measures to support and encourage the greening of our industries. These measures put companies at a disadvantage due to the high costs they entail. Companies must navigate a labyrinth of standards and provide far too detailed information on several topics. While this is a good thing, enough is enough. Especially because European companies are still struggling to recover from the energy shock that began just three years ago after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Our competitiveness continues to be negatively impacted.

The ECB at the helm for the last 15 years

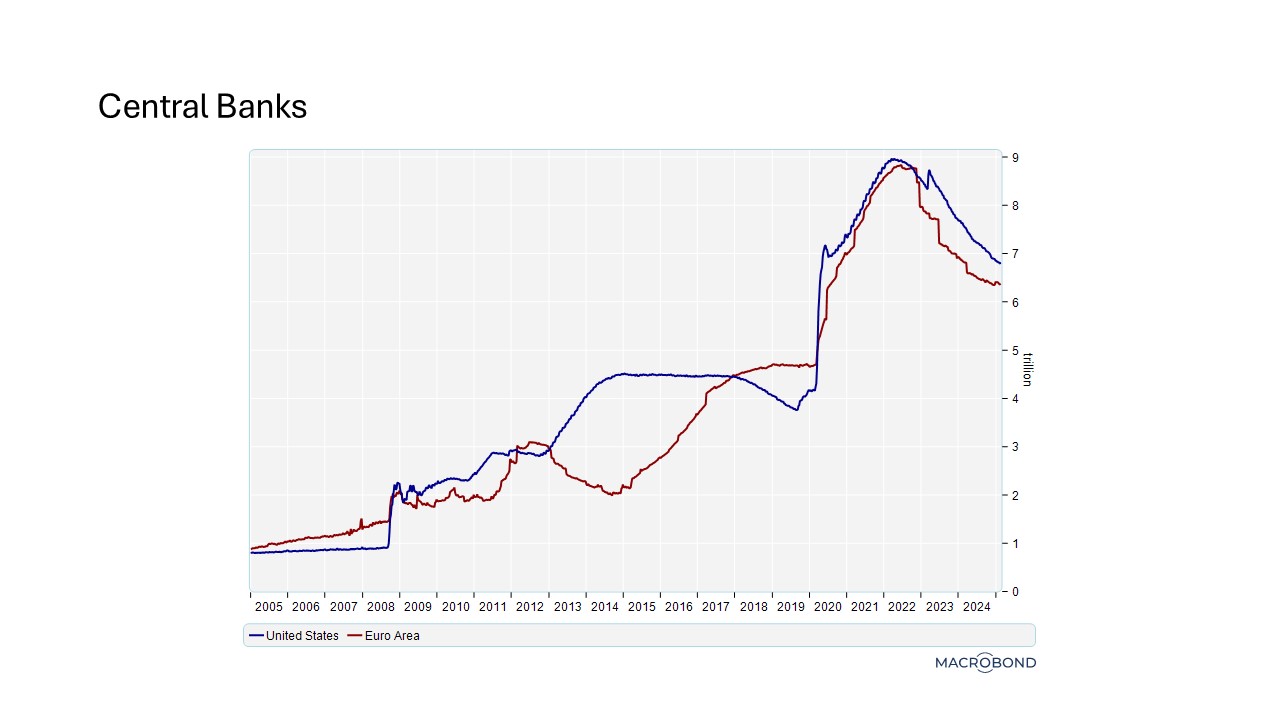

The European Central Bank (ECB) has played an important part in the many crises that Europe has experienced over the past 15 years. The 2008 financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis of 2012, the pandemic in 2020, and the energy shock necessitated an accommodative monetary policy. The main consequence of this was a drastic cut in interest rates, which caused both short-term and long-term rates to fall below zero in several countries. Because interest rates had been low since 2010 and further cuts were impossible, the ECB used its balance sheet as a monetary policy tool. This policy led to a massive infusion of liquidity into the economy. When inflation surged in the wake of the war in Ukraine, the ECB was forced to change course to curb inflation. That is why interest rates were raised several times. At the same time, the ECB changed tack to normalize excess market liquidity. It did so by gradually reducing its balance sheet. The fight against inflation seems to have been won. The time has therefore come to ease monetary policy to prevent the European economy from slowing down too much, especially now that a trade war with the U.S. seems to be on the cards. However, in terms of liquidity management, we see a continuation of the course that was set in 2022, namely a further ECB balance sheet reduction, resulting in fewer liquidity injections.

Abundant liquidity

The ECB's balance sheet is shrinking, although it is not yet back to the level it was before the first crisis. Far from it, in fact. So, what does this all mean? This is difficult to say, as history may repeat itself on many levels, but this does not apply to monetary policy. Never before have we experienced something similar, just like we never experienced an era of negative interest rates.

Low interest rates

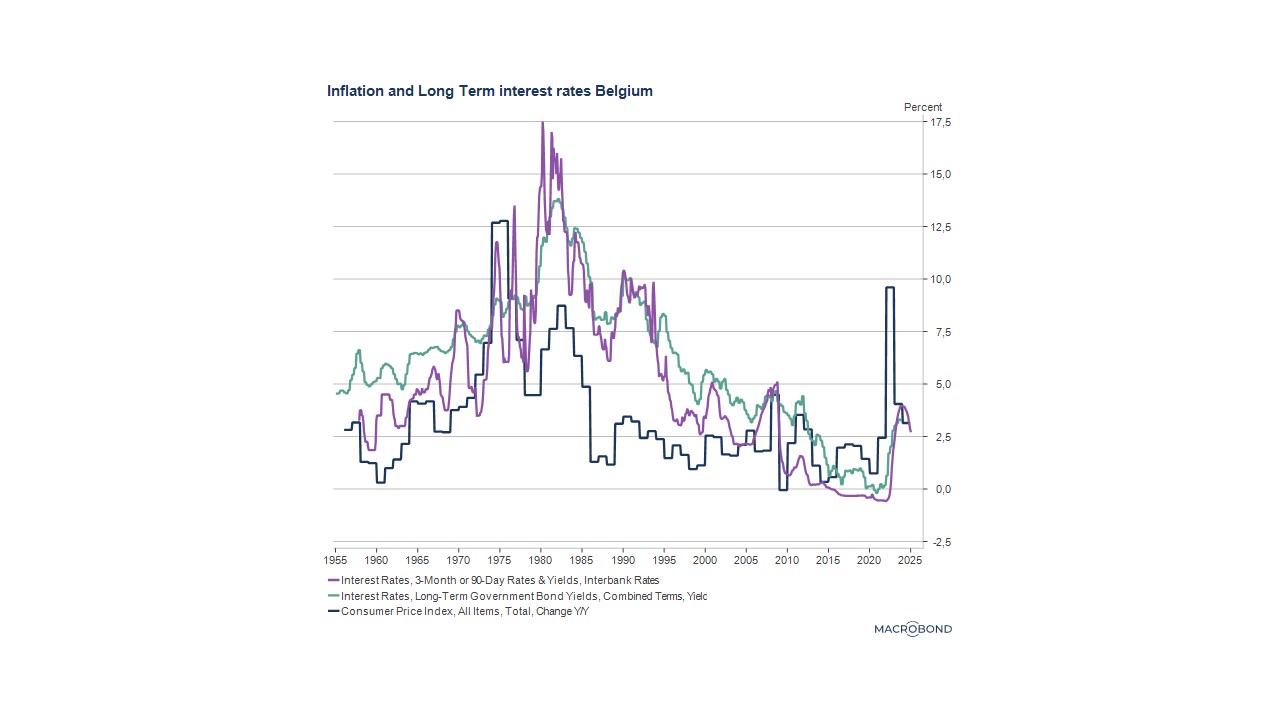

The most likely consequence of this situation of abundant liquidity is undoubtedly that it weakens the value of money somewhat, which means lower interest rates. If we look at the absolute level of interest rates at the worst time of the inflation surge in 2023 and compare it with the situation during the previous inflation shocks (1973 and 1979), we can see that both short-term and long-term interest rates have remained significantly lower. Admittedly, after several years with interest rates that had fallen to near-zero, the current rates may seem high. Especially to those who did not live through the years of the first oil shocks. But a historical comparison reveals there is a clear difference. When inflation was in the range of 8 to 12% in the 70s and 80s, interest rates fluctuated between 12 and 15%, compared to an interest rate of just 4% during the recent energy shock caused by the war in Ukraine. Nevertheless, this gave rise to inflation levels that were much closer to past inflation peaks of the 70s and 80s.

Food for thought.

The opinions in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of BNP Paribas Fortis.