Is US monetary policy too tight?

5 min

President Trump is making no secret of his desire to oust the Fed’s chairman, arguing that he is always fighting yesterday’s war and that it is high time the Fed cut rates, which it is reluctant to do until it has more clarity on future inflation.

In the last few days, we the picture regarding the infamous Trump tariffs has become clearer, now that the US has agreed deals with countries with which it has the largest trade deficits: Mexico, Vietnam, Japan and now Europe, which in the end will see a 15% tariff applied to all its exports to the US.

Future movements in US interest rates will play a crucial part in what happens next: obviously, lower rates would allow faster US growth, but this begs the question of whether current US monetary policy is really restrictive and whether there is any evidence that the Fed’s policy is too tight.

Historically, we know that if inflation is around 2% then the US Fed funds rate should also be around that level, otherwise imbalances appear in either direction. Looking back to the post-Covid period, inflation rose sharply as supply chains returned to normal and as a result of the war in Ukraine. The Fed failed to understand that the rise in inflation was more secular than it first appeared, and the bond market suffered one of its worst crashes when it became clear that monetary policy was lagging behind inflation. We also know that the Fed has been known to wait too long to cut rates when inflation has been falling and approaching 2%: for example, this resulted in a severe recession in the 1980s. President Trump wants to prevent history from repeating itself at all costs, which is why he wants to see lower rates as soon as possible.

Is policy too tight?

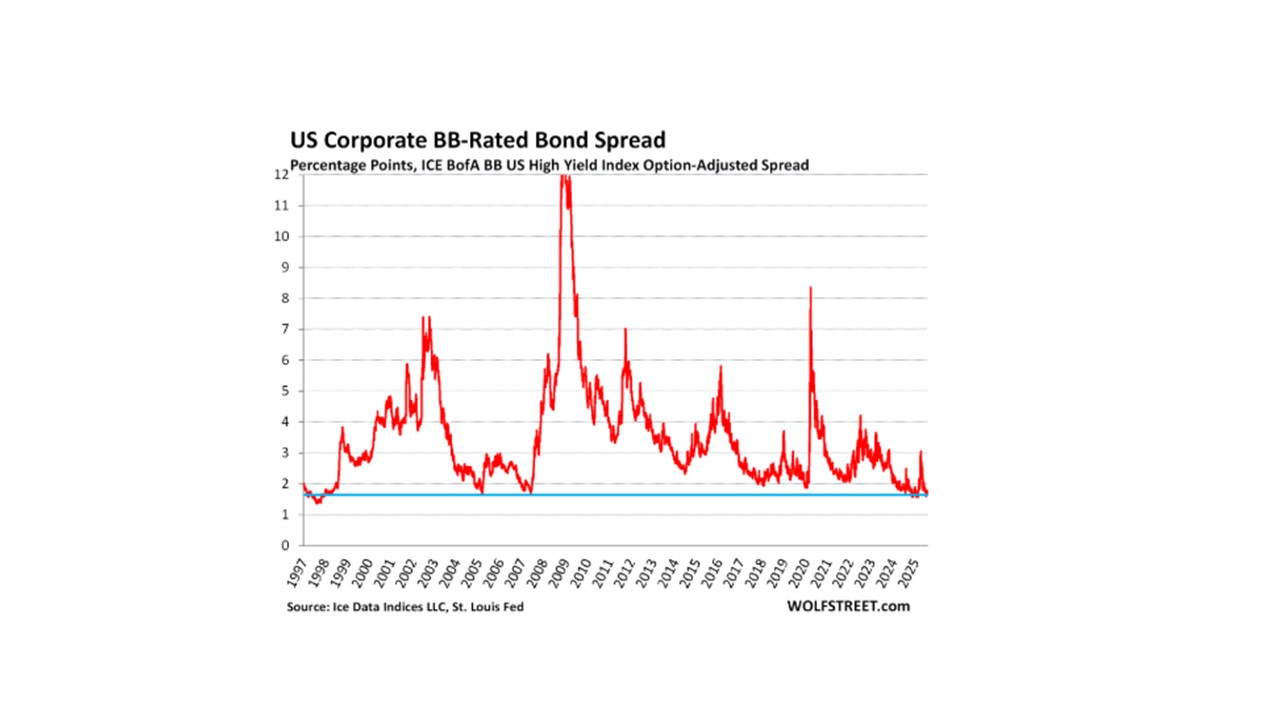

We know that inflation may rise because of tariffs, which explains the Fed’s caution. However, one chart has caught our attention: it shows movements in the spread between the risk-free rate (the yield on US Treasuries) and the yield on lower-quality bonds, i.e. those issued by companies with poor ratings (BB- or lower), often referred to as “junk bonds”. That spread is currently very narrow, close to an all-time low. This is obviously because risk-free bond yields have risen since President Trump’s return to the White House. However, it also means that investors are not demanding great rewards for the risks they are taking by lending to poor-quality companies, otherwise they would be asking for a much higher yield. It also means that they are not worried about an imminent recession...

Should we be worried about this narrow spread?

In the past, there have been several periods of very narrow yield spreads between risk-free bonds and junk bonds. However, the last time it happened, subsequent events were catastrophic for financial markets and investors.

In 2005 and 2007, when the spread was similar to current levels, we were on the brink of a major financial crisis and the global banking system was about to collapse, taking everything else down with it. Investors learned to their cost that they had been ignoring the risks, and they paid dearly for it.

When the Fed, confident that inflation had calmed down, cut rates for the first time in the current cycle in September 2024, the markets anticipated more cuts to come. However, they did not know that Donald Trump’s election victory was about to embroil them in an unprecedented trade war that would cause shockwaves in the equity market and a wave of panic in bond markets. At the time, however, the yield spread between risk-free paper and junk bonds was very narrow. It widened briefly in the turbulence surrounding “Liberation Day” in April 2025, but narrowed sharply again in July 2025.

What can we expect?

The current narrow yield spread between risk-free and junk bonds suggests that markets are very confident about the future, otherwise the spread would be wider. It is true that equity markets have rallied strongly since the calamitous start to the Trump presidency. From that, we can now deduce that if monetary policy was indeed too tight, investors would not have shown such confidence in either the equity or bond markets. We know that liquidity is still abundant everywhere, because central bank balance sheets are still much larger than they were before the various crises seen in the last 15 years. The Fed is probably right to wait a while before resuming rate cuts, but it seems obvious that, with the trade deals that have been reached in the last week, the risks of a surge in inflation seem to be much lower than before. So rate cuts could be on the horizon in the autumn.

However, we advise keeping a close eye on this, because there have been a huge number of plot twists in the last few months.