Europe’s competitiveness problem #3

2 min

Europa loopt achter in tal van technologieën. Waar het wel nog een voorsprong heeft, is in de ontwikkeling van cleantech en circulaire oplossingen. Maar de uitdagingen zijn groot, want ook daar is de Chinese technologie vandaag veruit de goedkoopste. Daarenboven wordt er een aanzienlijke overcapaciteit verwacht: tegen 2030 zou de jaarlijkse productiecapaciteit van Chinese batterijcellen en zonnepanelen respectievelijk eenmaal en tweemaal de globale vraag dekken. De productie van elektrische voertuigen neemt aan eenzelfde tempo toe. De Chinese overcapaciteit blijft enorm ondanks toenemende faillissementen. De gezinsconsumptie blijft daartegenover ondermaats, wat de uitvoer van die overcapaciteit stimuleert. Alsmaar meer landen introduceren bovendien tarifaire en niet-tarifaire barrières door de vermeende oneerlijke concurrentie van China. Het gevolg is dat China nog meer van zijn overcapaciteit naar de EU-markt sluist.

Enough of the laissez-faire approach

Europe now faces some tough decisions on how to pursue its decarbonisation efforts without completely undermining the competitiveness of its industries. The American approach of systematically excluding Chinese technology is unlikely to work in Europe. Such a strategy would slow the energy transition and make it far more expensive. Moreover, it would provoke strong countermeasures. Unlike the US, where only 20% of industrial GDP is exported, a third of Europe’s industrial production is destined for non-EU markets. This means the cost of such a strategy would be much higher for Europe.

However, continuing the laissez-faire approach of the past is also no longer an option. As a European Central Bank (ECB) simulation shows, such a path would seriously threaten employment. If the Chinese electric vehicle industry follows the same subsidy-driven trajectory as its solar panel industry, EU domestic EV production could shrink by 70%, while the global market share of EU manufacturers might decline by 30%. This is critical, given that nearly 14 million people are directly and indirectly employed in the EU automotive sector.

It’s worth remembering that the European Green Deal was designed to create new green jobs. Losing the clean tech sector would undermine future productivity growth, while the decline of energy-intensive industries would jeopardise economic security and increase Europe’s dependence on foreign actors. For example, Europe’s food security could be at risk if the fertiliser industry – an energy-intensive sector – were to collapse.

A different strategy for different industries

A one-size-fits-all approach for all industries is not viable. Europe must adopt a combination of strategies, as outlined in the Draghi report, which identified four distinct approaches:

- In sectors where the cost gap has become insurmountable – often due to high foreign subsidies – it may be more practical to let foreign taxpayers continue bearing these costs and import the technology cheaply. To mitigate economic dependency, Europe should explore diversifying its suppliers. However, such a diversification strategy comes with additional costs.

- Sectors like the automotive industry are essential in terms of employment. The origin of the underlying technology matters less in these cases. The recommended policy mix combines encouraging foreign direct investment with trade measures that offset the cost advantage created by foreign subsidies. Protecting the automotive sector could combine import tariffs with Chinese investments in the European automotive industry. Over time, import quotas could even be negotiated with China.

- For industries of strategic importance, the EU must ensure companies retain the necessary know-how and production capacity to scale up in times of geopolitical tensions. Long-term investments in these sectors can be encouraged through requirements for local content. Technological sovereignty can also be preserved by obliging foreign companies to form joint ventures with local firms if they want to produce within the EU. Which industries qualify as strategically important may change over time.

- In high-growth sectors where the EU has an innovative edge, there is already a clear roadmap. This involves deploying a range of trade protection measures until these industries have achieved sufficient scale, at which point the protections can be withdrawn.

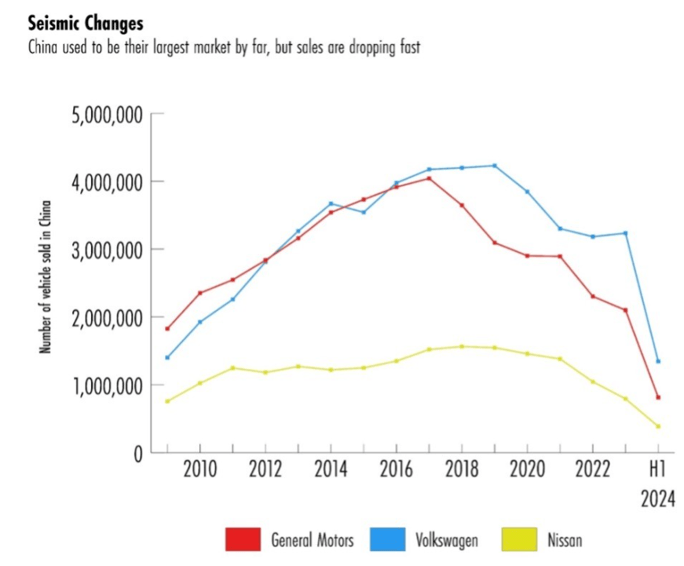

The most politically sensitive sectors fall under strategy 2. While Europe’s direction is clear, the transition is likely to be painful. The long-standing symbiotic relationship between China and Europe – where European firms gained market access in exchange for sharing technology – no longer works. “Yet companies like BMW still derive 40% of their profits from China,” notes China expert Pascal Coppens. “Moreover, 70% of the components for their EVs are produced in China.” Under these conditions, withdrawing from China would be very challenging, even though sales there are declining and competition is fierce.

The problem for European automakers in China is that much of the supply chain is also based there. Rebuilding such a supply chain and ecosystem elsewhere would be expensive, time-consuming, and, according to Coppens, largely pointless. “Pulling out of China means losing touch with the latest innovations. China is a generation ahead in applying digital technologies like automated parking, connected traffic lights and robotaxis. And when it comes to EV batteries, China is multiple generations ahead.”

The impact of import tariffs is also counterintuitive: they apply to cars BMW manufactures in China as well as to other European products. In other words, Europe is imposing tariffs on its own companies’ products. Yet Chinese-made cars remain highly competitive in Europe due to their low production costs, even after tariffs.

How will this unfold? “European carmakers will likely strike collaboration agreements with Chinese manufacturers,” Coppens predicts. “This will lead to the development of a new supply chain for EVs within Europe. Chinese firms will gain access to our markets, and technology exchange will become part of the deal.” This demonstrates how quickly stagnant regions can be overtaken in a world of constant change. The old symbiosis may be reborn, but this time the power dynamics will have shifted.

The opinions in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of BNP Paribas Fortis.