Euro Area economic outlook fractures further

5 min

Following the recent announcement of the US-EU trade deal, the short-term growth outlook for the eurozone remains uncertain. Professional economists, whose forecasts usually converge towards the end of the year, continue to disagree about this year’s EA growth. The era of the single-point GDP outlook seems to be over, at least for now. It is time to turn to a more scenario-based approach.

Historically, growth forecasts in the ongoing year tend to converge as the year progresses. This is a feature, not a bug: subsequent national account releases confirm actual quarterly GDP growth throughout any given year. Consequently, fewer data points remain for forecasters to disagree on, which mathematically enforces convergence on their full-year outlooks.

2025 however is different.

Convergence always happens eventually

To better understand forecast disagreement, we analysed an extensive set of professional forecasts, kindly provided by Focus-Economics. This data includes individual GDP forecasts by over 130 financial institutions, think tanks, and other international organisations. The data set begins in October 2010 and runs to the most recent edition of Focus-Economics’ monthly consensus publication, dated August.

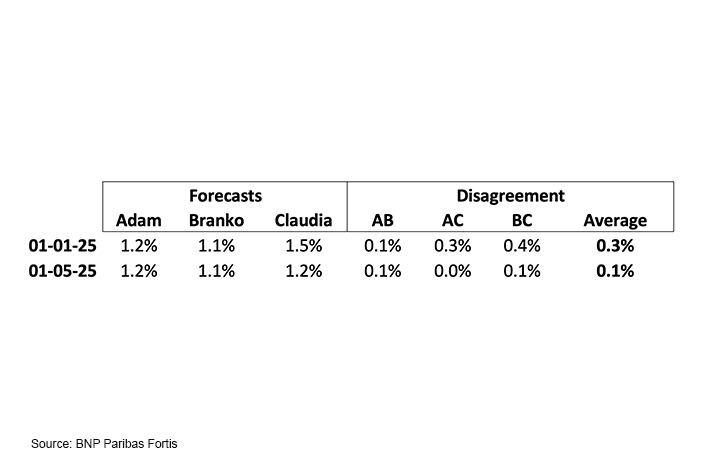

For each publication, we then calculated the average absolute paired forecast difference as a metric to gauge forecaster disagreement. An example can illustrate this approach. Suppose economists Adam, Branko and Claudia each make predictions for growth in the current year. They make their predictions at the start of the year and again in May, after the release of first-quarter GDP growth estimates.

Adam (1.2%) and Branko (1.1%) start the year in close alignment. Claudia has a higher growth figure in mind. Column “AB” shows the absolute difference in forecasts made by Adam and Branko, which in January is lower than that between either of them and Claudia. The result is an average absolute paired difference of 0.3%.

After some preliminary Q1 growth results are published, Adam and Branko confirm their outlook. Claudia, in contrast, adjusts her outlook after learning about the Q1 growth number. Consequently, the disagreement in columns AC and BC decreases, ultimately resulting in a lower average disagreement in the final column.

This stylised example clearly demonstrates the expectation that disagreement in forecasts should decline throughout the year. And the data supports this conclusion. For Euro Area GDP growth, disagreement in forecasts typically declines from around 0.3% at the start of any given year to 0.1% by the end *.

But not so in 2025

The times they are a-changing

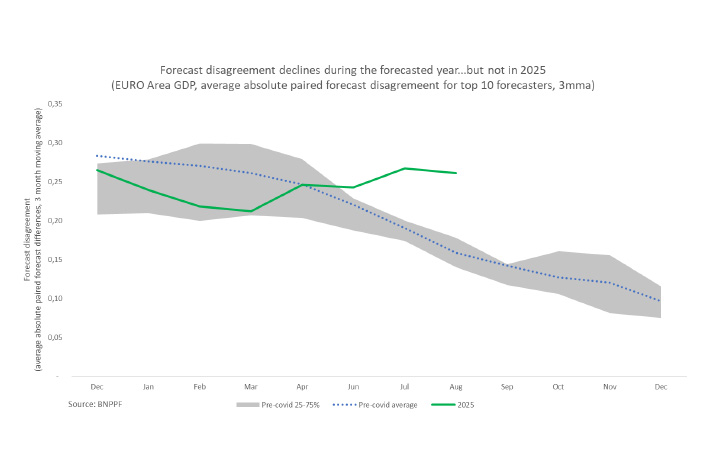

The graph below plots the average disagreement during the pre-Covid period in our dataset (2013-2019). The grey area indicates the interquartile range for these years, further cementing the trend of converging outlooks, particularly from the second half of the year.

The green line for 2025 clearly stands out. A decline in Q1 was followed by an increase in disagreement in April. No doubt, the tariff announcement in the month forced many forecasters to recalibrate their expectations. From then on, disagreement remained high. Currently disagreement is about twice as high as in the reference period.

So what does this imply for the state of the European economy?

Persistent and strong disagreement over whether the economy will grow and by how much impedes the consensus that informs policymakers, business leaders and individual households about the important investment and other decisions they are making.

Eventually, disagreement on 2025 growth will decline as Q3 and Q4 numbers are released. However, we are already seeing significant disagreement on the growth outlook for 2026. The era of the single, broad-based GDP outlook appears to be over, at least for now.

From a single point to multiple paths

One potential solution lies in the more extensive use of scenario thinking.

Recent research shows that such an approach can help organisations to make sense of future uncertainties more effectively. Having investigated 133 French health sector companies, Biuhalleb and Tapinos concluded that scenario planning increased preparedness and, perhaps surprisingly, risk taking. The authors claim that the perception that the future and its uncertainties, and their causal relationships are better understood creates organisational confidence in preparing for the future.

* At the end of the year, the final GDP growth figures for the first three quarters are typically published, leaving just the fourth quarter outlook uncertain. Furthermore, we have excluded the pandemic period (2020-2023) as the impact of sudden lockdowns caused significant but often temporary spikes in the disagreement metric.