Does the Belgian population believe in government austerity measures?

3 min

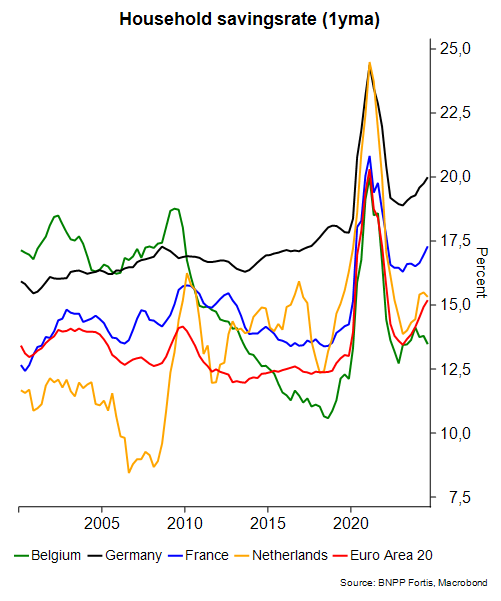

Since 2010, savings ratios – the share of disposable income that is not spent – have been increasing across most of Europe, except in Belgium. While private consumption benefited as a result, will this continue to be the case in the future?

During the Covid lockdowns, we saved at a record pace. This wasn't surprising, given that many opportunities to spend were restricted or unavailable. And in many European countries, this higher savings rate has persisted.

Looking at the bigger picture, it's clear that savings rates have been increasing in most European countries since 2010. Even excluding the Covid period, the amount saved as a percentage of disposable income is now significantly higher in almost every country than it was 15 years ago. But Belgium is an exception. What's behind this difference?

Savings motives

Research identifies several reasons why people save. We'll examine three key theories, each proposed by a different economist: Keynes, Pigou, and Ricardo. Can any of these theories help explain why the Belgian savings rate has declined?

1. Keynes formulated the precautionary motive: in difficult economic times, families save more. In other words, they create a buffer. Keynes's explanation would make sense if our economy was doing better than other economies. This is not corroborated by economic figures, at least not for the entire period. Moreover, consumer confidence in Belgium is roughly in line with that of our neighbours.

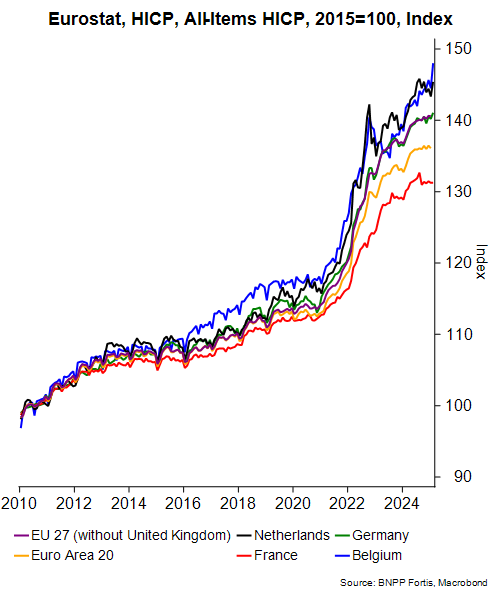

2. Pigou, on the other hand, considers savings to be a reaction to inflation (or the lack thereof): a sudden surge in price growth erodes the real value of savings. To stay on the same (real) growth path, people must temporarily save more. Did households make additional savings efforts in response to higher inflation in accordance with the Pigou effect? In that case, the high Belgian inflation (see below) should have led to more savings than elsewhere. But this was not the case.

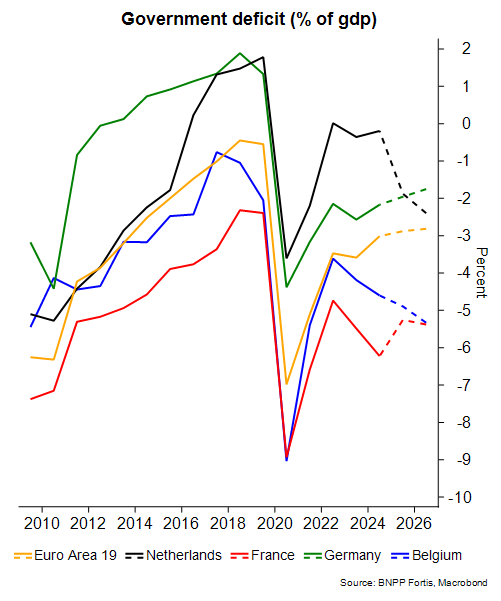

3. Finally, Ricardo lent his name to the theory of Ricardian equivalence. This implies that households are 'seeing through' public spending (intended to stimulate the economy). They realise that they will have to repay this government money at some point. This is why they save money and anticipate future tax hikes. These days, the Belgian public deficit seems to be competing with France in terms of negative attention from credit agencies. And this has actually been the case for quite some time. This would also imply a higher savings ratio than in most other European countries.

An interesting footnote to this question is how credible the consolidation efforts of successive Belgian governments have been. Ricardo’s theory assumes that families are anticipating a tax increase, which is necessary to balance the government's budget. But if households no longer believe that the government will actually increase taxes, then anticipatory saving becomes unnecessary.

Communicating vessels

So, what explains the lower savings rate? Since 2010, it's clear that more has been saved: the increase in the amount saved in our country was slightly lower than in the entire eurozone. Disposable income (the denominator of the fraction used for calculating the savings ratio) also rose at a slightly faster pace in Belgium compared with our European neighbours.

This means that there was more ‘non-saved’ income in our country, or in other words: higher consumption. This is also apparent from the figures: private consumption – the main driver of our GDP growth – has risen much faster than the eurozone average since 2010. High inflation continues to be the main cause for this, but volume growth was also almost 10 percentage points higher over that period.

The importance of domestic demand in general and private consumption in particular will undoubtedly continue to increase for our country in the coming period. This is a consequence of global uncertainty, which has been a drag on our trade balance and on companies’ appetite for investment.

To this end, other European countries are now one step ahead of us. When their higher savings rate normalises, it could give private consumption a boost. Might we get a similar boost from the ‘making work pay’ policy of the new government?