From entrepreneur to employer

2 min

More people at work - this is once again the motto of the new government. And it's necessary, too, to reconcile our way of life with the budget deficit. Our country currently has over four million employees, plus just over a million self-employed individuals. The latter group has increased significantly in recent years, as has job creation in non-market sectors. But what about employment in companies?

Job creation by companies

A recent IMF report takes a critical look at Belgian start-ups. It shows they are less dynamic than in other eurozone countries: birth and death rates are lower than the EU average. Also, young and fast-growing companies in our country have a much smaller share of total employment.

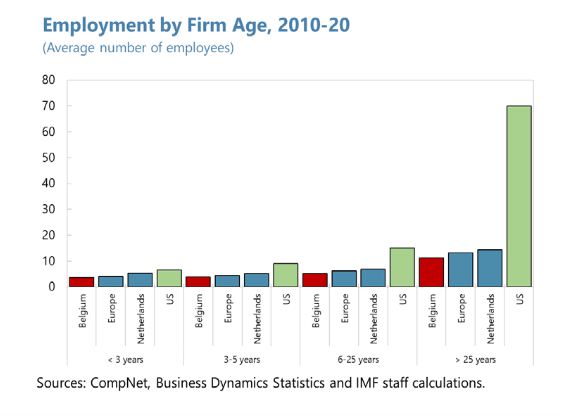

This is the case for the entire population. The graph below shows the average employment per country for companies in different age groups. In addition to the success of the US in every category, it is striking that Belgium consistently scores lower than the Netherlands and the European average.

Role of policy

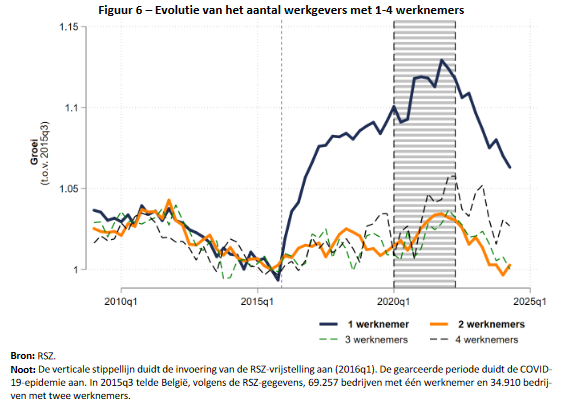

In our country, “entry-level” employers have received numerous incentives to hire their first employee since 2016. This takes the form of a permanent reduction in labour costs for that employee, through a discount on the employer's contribution to the National Social Security Office (NSSO).

The University of Ghent has examined the impact of this measure. Since its introduction, the number of starting employers-entrepreneurs who make a first hire has increased by 31%. As a result, 7% more companies had exactly one employee in 2019. There was no increase in companies with more than one employee.

It is also striking that new employers are, on average, less successful. According to the Ghent researchers, these companies hired fewer employees, had lower turnover, and created less added value than companies that would have hired a first employee, even without the exemption.

Choices, choices, choices

These figures were recently confirmed by the National Bank of Belgium (NBB). They model the increase in companies with one employee, assuming a constant labour force. Their estimate is that in such a situation, wages would be slightly increased (+0.5%). This is a result of the increased demand for labour from new employers.

However, this reallocates labour from productive to less productive companies. The tax shift distorts the labour market. As a result, total output decreases slightly (-0.01%). The managers of the one-employee companies benefit from the analysis, with their income increasing by 6.5%.

The big loser? The public authorities who finance all of this. In 2023, the measure cost 488 million euros. As new companies are constantly being set up, the cost will continue to rise if the policy remains unchanged, according to the Ghent economists, until all companies have subsidised their first employee. Given the current budgetary situation, they support abolishing or phasing out the measure.

The NBB's perspective is more nuanced. While its economists acknowledge the potential benefits of recruitment by self-employed individuals, they also suggest that such efforts can bring non-monetary benefits, such as a stronger social fabric. However, these broader benefits appear to be taking a backseat as the focus shifts to finding new resources to meet various obligations, including the NATO target of spending at least 2% of GDP on military expenditure.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of BNP Paribas Fortis.